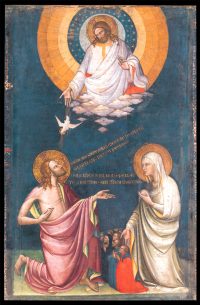

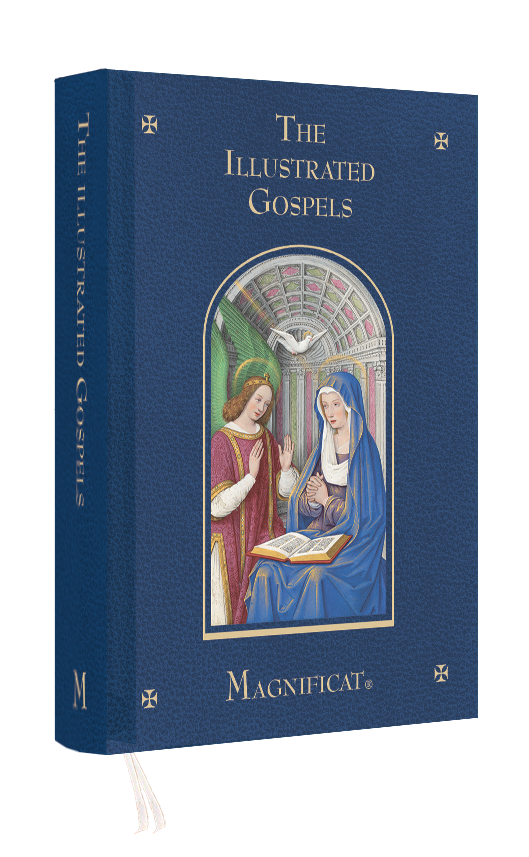

The Intercession of Christ and the Virgin,

attributed to Lorenzo Monaco (Piero di Giovanni)

(c. 1370–1425)

In a moment of rapturous love, Saint Francis of Assisi composed a hymn of praise to Our Lady, which begins with a striking list of her glories: “Hail, Lady, holy Queen, Mary, holy Mother of God, you who as a virgin have been made the Church!” The early-15th-century Camaldolese painter Lorenzo Monaco may not have been thinking of these exact words when he created his breathtaking Intercession of Christ and the Virgin, but his painting unveils their inner meaning with an unsurpassed richness. To think of Mary is to think of Christ—and of his Body, the Church.

The virgin intercessor

Mary kneels in the right-hand corner of the painting, draped somewhat unusually in a cream-white garment, which reveals in its folds a lining of regal yellow. Her golden halo calls attention to the reflecting glimmers of divine light that adorn her drapery, from the sunburst on her shoulder to the paradisical flowers traced delicately into the cloth: This is the Queen of Heaven, the woman clothed with the sun (Rv 12:1) whose physical presence refracts, prism-like, the infinite glory of God.

Yet, in Monaco’s vision, Mary’s unique dignity does not set her at a distance from the plight of ordinary men and women, but rather sets her free to be a true Mother for every believer. She gazes with simple trust at Christ, offering a prayer of intercession for the crowd of supplicants kneeling in the infinite distance between herself and her Son, whom she urges on with her outstretched right hand. In her left she holds her own breast, which is both exposed to sight and concealed from it by the flowing gauze of her veil—exposed because she is a true mother, whose own body nourished the body of the Incarnate Word, and veiled because she is a true virgin, who is even more blessed in having heard the word of God and obeyed it than in having nursed him at her breast (see Lk 11:27-28).

The one mediator

Jesus kneels across from Mary, draped in the red of his Passion, which wells out from the starkly emphasized wounds on his hands, feet, and side. His left hand gestures toward his Mother and her proffered breast, while he lifts his eyes and speaks to the heavenly Father, who in turn pours out the Holy Spirit upon the Son. Christ offers the Father his own gift of love: the wound he received on the cross, from which blood and water flowed for humanity’s salvation. The perfect triangle formed by the dramatis personae in the painting thus emphasizes Christ Jesus, himself human, as theone mediator between God and the human race (1 Tm 2:5), who receives the prayers of his Mother and all the faithful, lifts them to the Father, and pours forth the life of the Holy Spirit through his humanity.

The body of Christ is born

There is a second triadic relationship in Monaco’s painting, without which the first, more visually prominent one cannot be fully understood: the triangle formed by Mary’s breast, Christ’s side wound, and the gathering of worshipers at the bottom of the image. This is the body of Christ, unveiled as the Church born into the world. In one sense, the Church is born at the Incarnation, because the Word taking flesh in itself generates a community of believers: first Mary and then Joseph, who nourish the body of Christ—Mary by her mother’s milk and Joseph by his paternal labor. In another sense, the Church is born on the cross, when God dies for love of human beings and offers the water of baptism and the blood of the Eucharist as the means by which men and women will be drawn into his Sacred Heart and so become themselves members of his body.

Mary’s breast and Jesus’ side wound are thus revealed to be the means by which the body of Christ grows, once born in the flesh: first physically by Mary’s milk, then sacramentally by Christ’s blood. At the base of the image, between the two of them, is gathered the Church that comes to be from these two births and this double nourishment. Mary is Mother of the Church because she, in feeding Christ, is also the first to be fed by him in the life of perfect grace, and she is also Mother of the Church because all other believers are made members of Christ’s body by entering into the life of the Word who took flesh in her womb. She hands on to us only what she has first received from Christ, being the perfect disciple of Christ and the living symbol of all future Christians.

A Virgin made the Church

Monaco’s deepest insight in his image is that there is no such thing as divine life without communion, which means that there is no such thing as following Christ without the Church. In himself, God is not a God of monolithic isolation, but of the perfect union of three persons; when he conquered the legacy of our sins and made it possible for us to share his life in the Incarnation, he willed that our coming to him would have a distant but real echo of that perfect communion. Everyone who comes to be born in Christ is born of the motherhood of Mary, nourished by what she received from Christ, and led by her to deeper communion with him. With her as intercessor, we are made free to be fed by him; fed by him, we become his body, and so receive our share in the love of the Virgin who was made the Church.

Father Gabriel Torretta, o.p.

Dominican priest of the Province of Saint Joseph and doctoral student at the University of Chicago, where he studies the history of the theology of beauty in the Carolingian era

The Intercession of Christ and the Virgin, attributed to Lorenzo Monaco (Piero di Giovanni)

(c. 1370–1425). Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. Image: Public domain.

Additional art commentaries